Stephanie Smith rallied the troops.

They were assembling at the Cóbano municipal offices to take on a common enemy: glyphosate, the active ingredient in popular herbicides like Roundup. Their goal that day was to ban pesticide and herbicide use in public areas.

Smith was the first to arrive, and she practiced her speech outside the building. Her Spanish was a bit rough – she’d moved to Costa Rica only 10 months before – but she knew her enemy well. Smith, a British-American documentarian, is working on a documentary called “Just Another Brick in the Wall” about environmentally toxic schools in the United States.

“It’s about everything children are subjected to in schools,” Smith said. “From how building materials to food are all contaminated with glyphosate.”

Smith moved to Costa Rica with her family because she wanted to live in a more environmentally friendly country. That’s why she was surprised when one day she found herself flanked by men spraying pesticides on a public road.

“I was driving to pick up my son at school and then, to the right and to the left, there were two men manually spraying pesticides with no protection,” Smith said. “I had my windows down and the smell was so intense and horrific.”

Smith said one of the teachers at her son’s school felt lightheaded that day and her son got sick the following week.

“I came here thinking this was a green paradise,” Smith said. “I had no idea that pesticide use was so rampant.”

Costa Rica is one of the leading consumers, per capita, of pesticides in the world. In 2015, Semanario Universidad reported that the Regional Institute of Toxic Substance Studies (IRET) found that Costa Rica used an average of 18.2 kgs of pesticides per hectare of farmland.

China came in second place with 17 kgs per hectare.

Smith highlighted this point in her speech. By the time she started, the tiny municipal building was packed with government representatives and local residents, most foreigners who had relocated to Costa Rica.

She noted that she’d seen 2,4-D in Cóbano, which was used in Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant used by the United States during the Vietnam war that led to deformities and cancers in Vietnam and U.S. veterans. Smith mentioned a recent ruling in a lawsuit against Monsanto, the company that produces Roundup.

In the United States, a school groundskeeper with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was awarded $289 million in damages against Monsanto because he alleged glyphosate caused his cancer.

Despite that, glyphosate use has exploded in Costa Rica. A University of Costa Rica study found that glyphosate use in Costa Rica has risen nearly 50 times since it was first imported in 1982. That year, Costa Rica imported 36 tonnes of the herbicide. A total of 1,761 tonnes were imported in 2013.

Other municipalities in Costa Rica, such as Pérez Zeledón, banned the use of herbicides, Smith said. Why not Cóbano?

But the government responded with a question of their own. What about the farmers?

Aside from rich tropical forests, idyllic beaches and mountains, Cóbano is home to large swaths of farmland. About a third of Costa Rica’s rural population is employed in the agricultural, cattle and fishing industry and Puntarenas, the province Cóbano belongs to, is home to nearly 13,000 of Costa Rica’s 78,000 registered farms.

*****

Onias Alvarado remembers when people laughed at the idea that electricity would come to Cóbano. That was only about 20 years back, and he’s been farming even longer. His calloused hands and tanned leather face can attest to that. The 61-year old from Cóbano works the same farm his father did before him.

He knows cattle, too. It’s what has kept food on the table for generations. Land was cheap in the area back in the day, before the tourist boom. He remembers one family who sold their land piece by piece to fuel their drinking habit.

The rush back then was to cut down trees and make way for pastures to feed cattle.

“It was a shame, actually,” Alvarado said. “It was really beautiful, all those mountains.”

Alvarado remembers a government initiative that encouraged reforestation and led to hundreds of thousands of acres being reforested. Alvarado isn’t opposed to conservation or protecting the environment, but he still uses glyphosate throughout his 10-hectare farm.

He says he has no other choice. He can’t afford to farm any other way.

There are two main reasons Alvarado uses glyphosate. One, to kill weeds on his farm and occasionally make way for “pasto mejorado,” or Bracharia, a type of drought-resistant grass that can grow in most soils and is resistant to prosapia, a bug that destroyed grass throughout Cóbano years ago.

The other reason he uses it is to keep the road clear. Alvarado says farmers have to keep the area where their farm meets the road clear of any brush or growth.

This is known locally as “rondas.” Alvarado says he used to use a machete to keep it clear. It was tough work in the tropical sun, and it could take up to 10 hours to clear 100 meters of ronda.

Aside from the risk of wielding a blade for that amount time, Alvarado says you can get bad cuts if you strike a glass bottle, which happened frequently enough for him to want to find other methods. At this age, Alvarado says he’d hire someone to clear his ronda, something that would cost 1,200 colones per hour, or 12,000 colones for every 100 meters.

Or he could use glyphosate. He currently gets a gallon for about 6,000 to 7,000 colones and he can clear 500 meters of ronda with it. After he loads it up in his hand pump, he says it takes about 15 minutes to spray 100 meters of ronda.

The glyphosate also keeps the road clear longer, Alvarado says. Clearing it manually with a machete keeps it clear for around two months, while glyphosate keeps it clear for up to twice as long.

Alvarado tries to save money any way he can.

“The price of everything has gone up,” Alvarado said. “And then when the dollar goes up, everything goes up.”

While the cost of living in Costa Rica has risen steadily, the price of cattle has dropped. Alvarado says that five years ago you could get 1,800 to 2,000 colones per kilo for a good calf. Nowadays you can get 1,100 or 1,200.

He says cheap cattle imported from Nicaragua has hit local farmers hard.

Alvarado has tried to diversify his offerings. He produces honey and imports it to Europe. Their project is small though and they were able to produce 6 kgs of honey this year, netting them about 300,000 colones, or about $500.

The idea of banning glyphosate is frustrating for Alvarado because he doesn’t know what he’d do without it.

He says he’s never gotten sick from it and doesn’t know anyone who has. He knows people in rice plantations who’ve gotten sick, but he thinks it was because of the tall plants and airborne pesticides they used. Alvarado always uses the proper protection and a hand pump that doesn’t spray glyphosate into the air.

*****

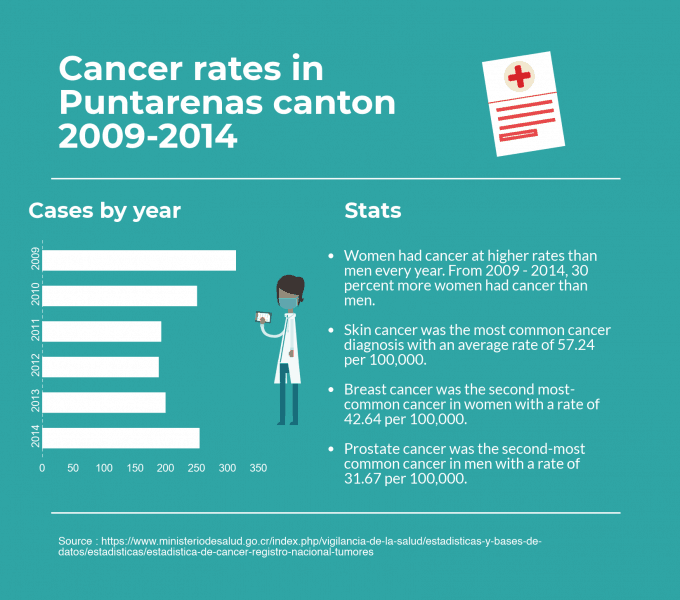

“There’s been no increase in cancers in the area,” said Dr. Juan Ledezma, an epidemiologist and head of the Peninsular Regional Health Authority, which oversees public health in Cóbano. “There’s no relation between the use of pesticides in public spots and cancer.”

While online records are only updated to 2014, Dr. Ledezma said he’s interested in analyzing more recent cancer statistics to see what the risk is in his community. Despite not having analyzed glyphosate use in the region, Dr. Ledezma agrees with other studies that have been done on the herbicide.

“[Glyphosate] has been proven to be carcinogenic in studies in other countries,” Dr. Ledezma said. “So how are we going to use it to kill weeds at schools or public areas?”

Dr. Ledezma says his main concern is with multiple exposures, especially the person applying glyphosate, such as municipal employees. He says we should limit the hours and places it’s used, but he’s also not opposed to banning the substance altogether.

“I agree with the people who want to ban it,” Dr. Ledezma said. “A lot of municipalities have already agreed not to use it.

“The only thing that’s doing is protecting the country. If we keep doing that, that’s great.”

While Alvarado’s farm is just 6 kilometers from Cóbano as the bird flies, it’s nearly an hour away as the car struggles to make it up steep rocky roads and rivers. One river crossing has a small wooden bridge built by locals. It’s small and can only fit one motorcycle at a time.

“We made it last year, two winters ago,” Alvarado said. “We got some teak trees and a Guanacaste tree and nailed them. I don’t think it’ll last another winter. It’s already rotting; one of the teak logs broke and you can fall in, motorcycle and everything.”

Alvarado says they’ve been asking the government to fix the original bridge for over two years. But if you don’t keep your ronda clean, the government will send a warning letter and then an employee to clean it up for you. Then they’ll quickly send you the bill.

Flooding is also common in the area. The Arío river runs right behind Alvarado’s farm; this season, it flooded his farm and sent uprooted trees hurtling through his land. He almost lost a horse, but there were no casualties this season. Debris from the flood still litters his farm, and the rainy season starts back up in May.

Many families in the area are one bad step away from financial ruin. There’s a goat farm that earned a Blue Flag certification for its environmental practices, close to Alvarado’s.

It belongs to Salvador Montero and his family. They have goats and make cheeses, yogurt and milk to sell in towns like Santa Teresa and Montezuma.

But in early November, their pickup truck broke down. Montero’s wife was going through menopause and couldn’t tend to the animals like she used to. Their output decreased and their costs only went up.

They need to get feed and supplies from Cóbano and with the car down, it costs 10,000 colones to get supplies, or as the Monteros think of it, a whole sack of feed for the goats.

Dagoberto Rodriguez, 47, who runs the local co-op, CopeCobano, hopes he can buy a truck, establish routes and deliver products to farms at a discounted price. He hopes the local co-op can make a comeback because sales have gone down recently. He carries glyphosate, but has been trying to switch over to organic herbicides to appeal to both sides.

They are more expensive, though. He thinks there’s also a solution that can be made with vinegar, but he’s worried farmers would just buy it from local supermarkets and hurt the co-op sales even further. Dago has big dreams for the CopeCobano. They have a small cafeteria on the side that sells empanadas, the best in town Rodriguez swears, and he can keep adding to it and turn it into a community center for the people of Cobano.

Rodriguez says was at the meeting at the municipality and said that while many newcomers are well-intentioned, they don’t realize how hard things are for the local population.

The farms are as close as they always were, but pulling further away as they stay stuck trying to survive while investment and tourist developments push towns like Santa Teresa and Montezuma further ahead.

“I’ve actually fumigated some people’s houses who were at the meeting [to ban pesticides and herbicides,]” Dago said. “Sometimes I feel like we’ve gotten to the point where we’re bothering the tourists.”

Alvarado said he never heard about the meeting concerning pesticides and herbicides at the municipality, which was attended by very few local Costa Ricans. He said he would’ve gone to talk about his side if he’d known about it.

He says that despite health concerns, he really doesn’t see any other option to do the work that glyphosate does on his land.

Smith says she understands there’s frustration with foreigners who have come and developed land without regard to the local population, but her motivation is what’s best for the environment, the people and future generations.

The group she belongs to, Costa Rica Libre De Tóxicos, is hosting organic agriculture workshops. She says the group wants to work with the government to educate farmers about alternatives. She also says despite contacting the municipality weekly, she still hasn’t seen or heard of any results stemming from the town hall back in early November.

“I hope that the farmers don’t take this personally. It’s not about them,” Smith said. “It’s about big agrochemical companies that are taking advantage of all of us.

“I see myself as a human being, not as an American, not as British, Peruvian or Tica. We are all in this together.”