In August, everywhere you turn there is some incredible event celebrating Afro-Costa Ricans and their profound historical contributions to Costa Rica.

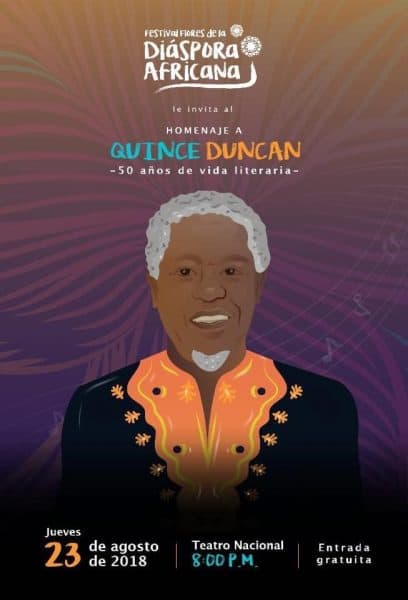

This year also marked the 50th anniversary of writing and publication for Quince Duncan, the preeminent Afro-Costa Rican writer. The entire month was framed as a celebratory salute to his prolific literary production as well as his nuanced political and intellectual presence over the last half-century.

Alongside the three main annual events — the Limon Roots Awards Gala, the Festival Flores de la Diaspora Africana, and the Grand Parade in Limon — other vital conversations were happening throughout the country.

One of the most important conversations I was fortunate to be a part of was hosted by Karla Scott, a blogger at Mi Vida Afro, about the intricacies of having and maintaining natural Afro hair.

The workshop was a hands-on discussion fused with personal testimonies alongside step-by-step processes about natural hair care and resources available in Costa Rica. Scott invited three presenters to share their experiences maintaining their natural, curly afro hair.

Presenters Ichi Wilson, founder of Natural Hair Sisters 506, Leimy de la Rosa, of Instagram´s The Curly Gang, and Wendy Pinnock, a blogger for Wenmeltv, shared a wide range of ideas on how to care for curly Afro hair with a packed room. It was a festival of conversation as the audience, predominated by mestizo mothers and their Afro-descendent daughters, soaked up the information on hair care.

The presenters also talked about the difficulties of childhood in Costa Rica, where conforming to the straight-hair look was almost mandatory. Life in Limon, which allowed for natural hairstyles like braids, cornrows, afros, twists, and others, became radically different when they moved to San José, where blackness was more of a novelty than the norm.

In order to protect themselves against the mean-spirited taunts by classmates or even on the street, many young Afro-Costa Rican women rushed to get an alisete (a chemical hair straightener) or weaves and wigs. It was a shield against inherent racism that fueled many of their interactions.

The decision to “return” to their natural afro roots, literally, as grown women is a radical personal and political statement of pride. The stigmas associated with Afro hair as being dirty, non-professional, and unkempt were flipped on their head as the wonderful and intricate job of caring for Afro hair was discussed.

The time was balanced between slide presentations about the impact of positive and negative visual representations with details of the correct comb to use, the various types of curls, examples of hair bonnets to sleep with, as well as rituals and practices on washing hair. A slide that mentioned that Sunday was washing and hair care day brought a collective nod amongst the black women in the room.

Scott kept a running list of natural hair products and recipes for making your own hair oils, as well as chemicals and preservatives to avoid in hair products.

Miami Cosmetics in San José was mentioned as a “go-to” spot, yet many of their products are imported from the U.S. and remain loaded with parabens and other ingredients that strip natural oils from Afro hair. Wendy Pinnock was able to share a variety of easy and versatile hairstyles and six lucky participants took home one of her fantastic hair oils as a gift.

Most important about this gathering was the unstated need for knowledge. It was clear that natural hair black women in Costa Rica had to be creative with products and hairstyles.

There was also a general undertone about acceptance as there is still a wall of bullying that makes it incredibly hard to celebrate your natural hair when the world doesn’t. Each presenter urged the audience, especially mothers with young daughters, to affirm the beauty of their child’s natural hair every day and under all circumstances.

These words will be a salve in spaces where differences mean shaming and not celebration. Positive images, historical knowledge, and claiming an Afro-descended history are simple steps in helping black girls in Costa Rica know they too are magic.

The same theme resonated throughout the National Theater in San José on Aug. 26 during the annual Limon Roots Awards Show. The show, along with the magazine Limon Roots, is the brainchild of Ramiro Crawford. Quince Duncan and the Mighty Gabby, master calypsonian from Barbados, were honored this year.

The highlight of an evening full of incredible African dance and music, was the play Negra Soy, directed by Sharifa Crawford and Erick Rodriguez. The play was a critical meditation on the price of being a black woman in Costa Rica.

Ten women, Allyson Maykall, Stephanie Westney, Krissia Oquendo, Stepahnnie Davis, Rosaura Davis, Alexa Morales, Maria Marchena, Ritha Clarke, Tamar Hines, and Cishel Crawford, told the story of growing up being taunted because of their curly hair, chocolate skin, and rounded noses.

They talked about being on the margins of Costa Rican society, especially in San José, where blackness and womanhood were symbols of vulnerability. Yet in that fragility, these women rose. The play’s narrative told how they, as a collective of beauty, finally came to claim all the things which once brought them shame: their sensuous curves, the curl of their hair, the sheer melody of their rich brown skin.

The voice of Stephannie Davis White, from the band Queens of Reggae, shaped the entire production with its power.

I was transported to my first youthful experiences visiting my grandma San José and hearing taunts of “morena” and “negra.” Those hurtful words were 20 years away though and I thought those times had changed when I moved here with my family four years ago. Yet my son spent the first month of school being called “Cocori” by classmates.

Some things change while much stays the same.

Acknowledging the legacy of Afro-descendants in Costa Rica also reminds us to be thoughtful about our daily interactions. Not everyone wants to be called “Negra” in the feria or on their Facebook message for their birthday. For some, being called by their skin color is not a term of endearment, even if it is an entrenched social ritual.

I find that as we broaden these types of affirmative, information-sharing conversations, they not only heal ignorance but confirm that people of Afro-descent bring invaluable wealth to the diverse Costa Rican table. I salute these magnificent Afro-Costa Rican women who are at the forefront of these discussions, raising the bar of humanity and insisting on visibility and value.

I too am proud to say Negra Soy.