See also: Costa Rica is for lovers – the affectionate language of daily life

When I worked in English-language education and visited an advanced young-adult class in San José, I asked them what their biggest challenge to language learning was. Lack of time? Mastering irregular verbs? The delightful traps with which the English language is laced, such as the multiple pronunciations of -ough, with no rules to follow whatsoever (think tough, bough, through, dough, cough)?

Nope. Their answer was none of these, and they all had the same one. El choteo, they answered in unison, a few sheepish glances flying across the room. When they opened their mouths to speak English, they told me, they knew that if they made a mistake, they’d be ridiculed by their peers. On the other hand, if they spoke perfectly, the mockery might be even worse – who do you think you are to speak so well? So they kept quiet, which is of course disastrous for a language learner. Their oral proficiency suffered because they were afraid to speak up.

To chotear is to take someone down a peg, to mock, particularly when people show aptitude for something or getting too big for their britches. “Uuuuuuuuuy,” you might hear if you’ve done something right, with the intonation that goes with a strut and a la-di-da hand gesture. It goes hand-in-hand with Costa Ricans’ love of fun and wordplay, but many Costa Ricans have told me it is also rooted in a cultural aversion to standing out, to individual achievement, to ego. On several occasions I’ve heard Costa Ricans compare this aspect of their culture to the famous analogy of the crabs in a bucket that pull down any fellow crab that starts to haul itself out.

Constantino Láscaris, in his excellent book El Costarricense, outlines this view of choteo as well, but ultimately dismisses it in favor of a lighter, more positive view. “El choteo is funny,” he writes. “The jokes might be good or bad, accurate, dirty or less dirty. But it represents an extraordinary popular wisdom. A people that tells jokes gives an outlet for passions… The President of the Republic is the delicious object of choteo, as well as all legislators, no matter who they are.”

I think both interpretations are probably correct. I have often been grateful for the fact that in Costa Rica, it’s tough for someone to get high and mighty, or to go to extremes, because someone will also be there to make fun. At the same time, I think it is also true that this might inhibit some people, and maybe even keep them from following certain passions.

I found myself reflecting on el choteo in an unexpected context recently, and in a beautiful place: San Gerardo de Dota, where, on a cabin dangling off the edge of a mountain, I read A Room of One’s Own for the first time. In air just about as cold and crisp as you can find in Costa Rica – which is to say, utterly delectable, demanding warm socks and wood fires at night – and in a silence that, aside for birdsong, is just about absolute, I read Virginia Woolf’s brilliant analysis of what happens to women who try to climb out of the crab bucket, artistically speaking.

I read Virginia Woolf’s imaginings of what would have happened to Shakespeare’s sister, if he had had a sister whose brilliance was equal to his own. In that patient, detailed way of hers, she paces through the possible actions Shakespeare’s sister might have taken in order to pursue her passion and live as a writer. No matter what thread Virginia pulls on, it does not end well.

Months ago, when my obsession with “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda was at its peak, I read that his family works to give him and his wife a support system, especially in terms of childcare. The article said something like, “Their priority is to make sure he has the space he needs to create.”

It sounded so delightful – and necessary, for all those of us who think that Miranda (speaking of Shakespeare’s relatives) is the Bard’s Nuyorican spiritual twin. I want his family to give him space to create. Please, provide him with whatever he needs to make the Next Great Thing.

I also want that space for myself. When I think about claiming it, though, I feel presumptuous. A voice says, “¡Ni que fueras Shakespeare! ¡Ni que fueras Lin-Manuel Miranda, mae! ¡Ni que fueras Virginia Woolf!” Ni que fueras: a classic choteo opening. “As if you were.” Think again. Come back down to earth. Ubíquese.

I am choteándome a mi misma, pulling myself back down into the crab bucket, which many people – particularly women, I’d argue – are all too good at.

But here, right here, as if she could hear my inner choteo, is what’s so brilliant about Woolf’s famous essay. She has doesn’t argue with these voices; she sidesteps them. She makes no pretense that everyone in her audience have works of genius stored within, waiting to pour out. Rather, she argues that no matter how talented we may or may not be, we all have a role to play. All books are the continuation of the books that came before, and all original thought, even if imperfectly expressed, moves the ball forward for the team she imagines of women writers throughout history.

She says that Shakespeare’s sister “would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile.” We must recognize “the common life which is the real life and not… the little separate lives which we live as individuals.”

The common life, which is the real life.

That’s why I think el choteo has an upside and a downside. It has an upside because the common life is the real life. No one of us is such a big deal, all on our lonesome. When we start to think that we are, it’s good for our friends and family to shake us out of it with a little humor. I can think of some people in my home country, the United States, who would be much better people – and leaders – if they were doused on the daily with some healthy choteo.

At the same time, each of us has a chance to contribute something to that common life. We do have a worthwhile reason to carve out what we need for that purpose: a room of our own, whether literal or figurative. We do have a mission to fulfill, because whether we produce masterpieces or only mediocrity, we have a shot at providing the next genius, Shakespeare’s sister, with a boost. A leg up. A starting point a little further down the road.

So to every tentative English student, every aspiring writer, every one of us feeling a little pretentious as we claim our space as artists or thinkers or learners, I think Virginia would say, if she were here in Costa Rica: accept your fair share of choteo with a nod, and let it keep your feet on the ground, rooted in our common life. But after that, simply carry on. Don’t stop. Create something. No matter what they might say.

Read previous Maeology columns here.

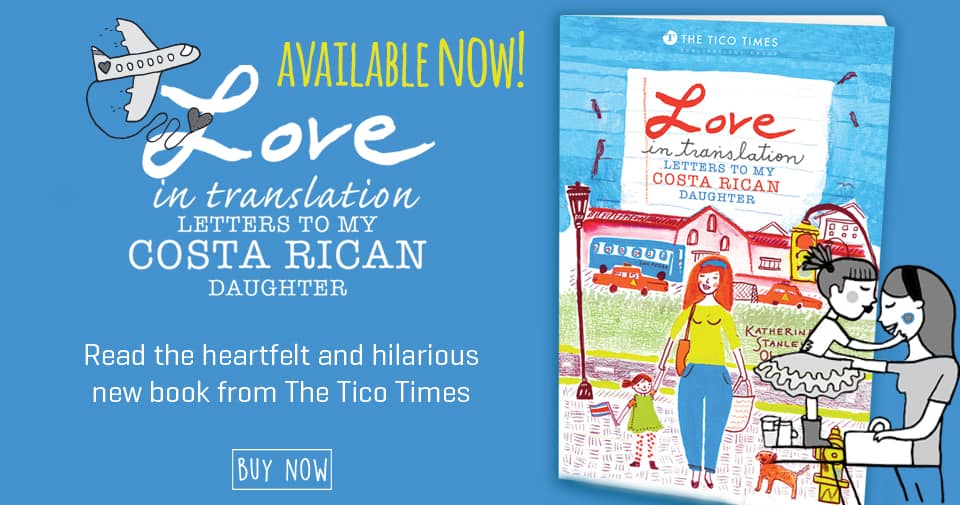

Katherine Stanley Obando is the editor of The Tico Times and the author of “Love in Translation: Letters to My Costa Rican Daughter,” a book of essays about motherhood, Costa Rica’s unique street slang, bicultural parenting, and the ups and downs of living abroad. She lives in San José. For more from Katherine about Costa Rican life and culture, follow her on Facebook or Twitter, or subscribe to the Love in Translation blog.