Most weeks, I aspire to examine Costa Rican language and culture with as much subtlety and sensitivity as I can muster. Most weeks, I hope that my bumbling travels through this linguistic wonderland are conducted with some modicum of class and grace. But not this week.

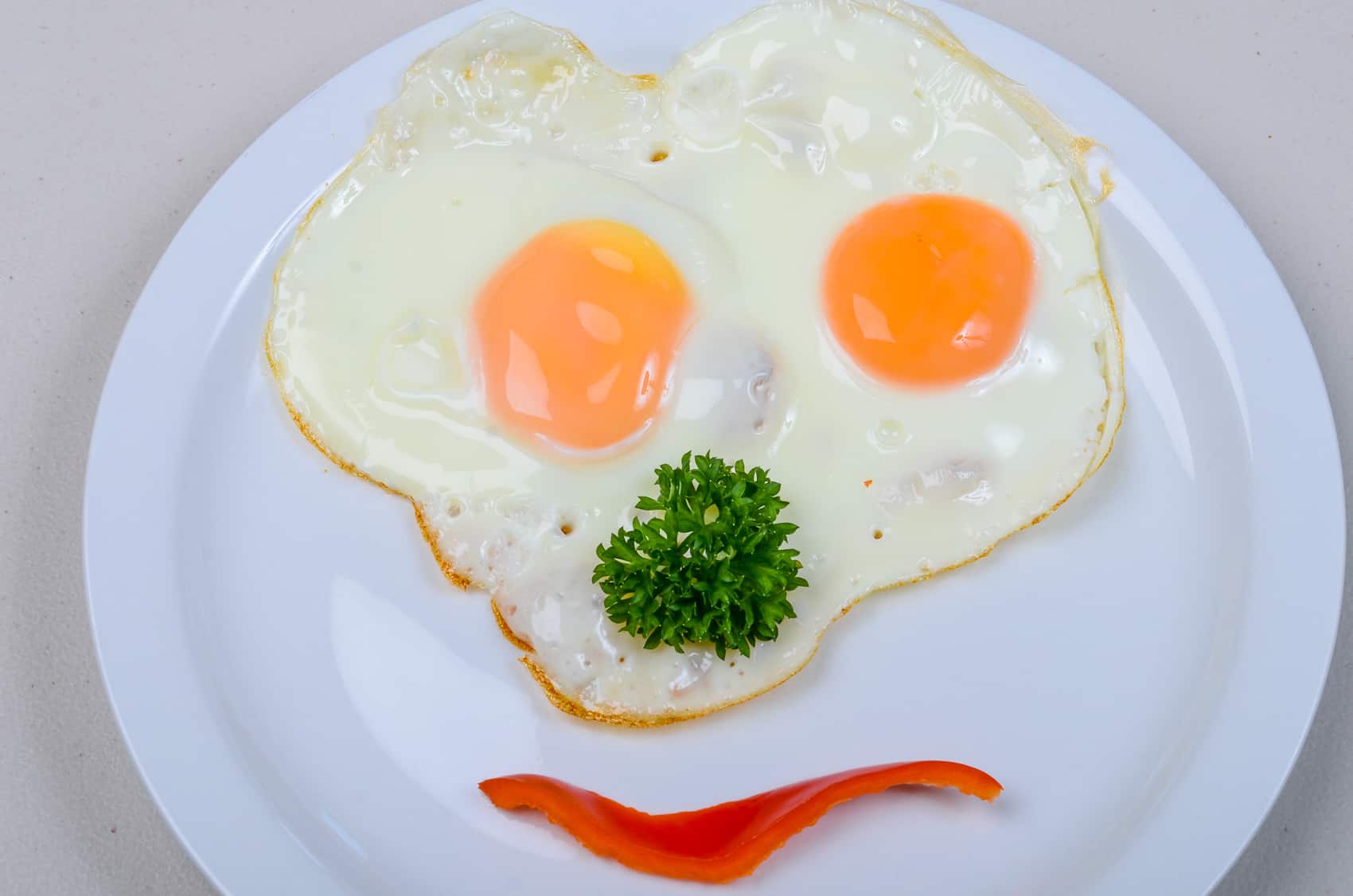

This week, we’re getting down to business – because at some point, you’ve just got to grab the Spanish language by the huevos. I’m sorry, but it has to be done, because if you live in Costa Rica, you might sometimes yearn for sharp cheddar cheese or real maple syrup, but you will never, ever want for eggs, whether in your kitchen or in the language you hear every day.

The sale of eggs on the streets of Costa Rica is infinite, and infinitely annoying (when I watched the film “El Regreso” in the theater, a rant about el mae que vende huevos got the biggest laugh of the night). I don’t know about wealthy enclaves or rural areas, but on many run-of-the-mill San José streets, the blissful silence of early morning is splintered daily by horrendous calls of “¡Huevos huevos huevos huevos! ¡Llegaron los huevos!”

We’re talking megaphones and pre-recorded messages blaring from battered old sedans where soon-to-expire eggs bounce along in the hot sun all morning. On our street, at some points there are three egg cars every single day, each selling eggs in packages of 30, which makes me wonder who is eating them all. Is the 500-pound man hidden in one of these little houses? Is there an NFL defensive line boarding with the nice old lady across the way?

Who knows, but it’s fitting that there are eggs practically rolling down the streets, because they are a central part not only of the way Costa Rica eats, but also of the way it talks. The word huevos, of course, has a secondary, anatomical meaning that is pretty central to the use of Spanish in any informal setting.

There are some equivalent expressions in English: We say, “It takes balls to drive in Boston,” just as you need huevos to drive in San José; we say that someone is “ballsy,” or that someone needs to “strap on a pair,” and other versions of this. But in Spanish, the nuances and iterations are seemingly endless and pretty much ubiquitous.

Some phrases are obvious. You can ponerle huevos – be courageous, stand up for something. You can hacerle huevo – get the job done. You can have a dolor de huevos, which is, well, a real pain. But then there’s huevón, or güevon, which begins to lead us into the untranslatable neighborhoods of egg linguistics.

Huevón can be a commonplace greeting among male friends, or it can be a description of someone who is lazy, stubborn, a pain. The latter usage is often accompanied by a certain a two-handed gesture, of course, and the energy with which that gesture is made conveys the degree of annoyance. Qué huevón ese mae. Qué señora más huevona.

And so on. My dad, born and raised in Guatemala, used almost no Spanish with me when I was growing up except the word huevona, which I got used to hearing whenever I was particularly lazy or frustrating. Along with a few other unprintable words, it was my first foray into Spanish, which probably explains a lot.

Then there’s ahuevado/a, a fantastic and singularly expressive word. To be ahuevado/a is to be bummed out, frustrated, down, done. Its perfect pronunciation still eludes me – it is basically a puff of vowels with the tiniest differentiation between the two “w” sounds of the h and v – but its “wah-wah” sound is the perfect accompaniment to the emotion it expresses.

The word can also describe the event or situation that has made you feel that way. For example, a dull party can be “ahuevada,” or when you hear your friend describe a frustrating situation, “Qué ahuevada, mae” is the perfect response.

Finally, there’s the king of them all, the number-one phrase I am often lost without when speaking English: manda huevo. I can explain how it’s used, but not why it means what it means (if any readers can provide a more direct translation, please let me know). From what I can gather, it is quite rude in many Latin American countries, but while it’s still uncouth in Costa Rica, it’s also very useful and even endearing.

It can mean something close to “come on!” or “for crying out loud!” or “seriously?” (as in, “What? You forgot to buy milk after I reminded you 50 times? Manda huevo”). It can mean “That’s so unfair” (“I cooked this whole meal and you can’t even clear the dishes? Manda huevo.” Yes, it has lots of matrimonial applications). Or, in its nicest version, it can express “But of course, it’s the least I can do” (as in, “Please, you don’t need to thank me for giving you a ride home after you painted my whole house for free. Manda huevo”).

I’ll tell you what really me ahueva. If the rating system for annoying noises is one to 10, one being an insistently clicking pen and 10 being Fran Drescher, then two of the egg men who frequent my street rate a five or so. The third guy rates a 50. He doesn’t use a recording, which at least has the virtue of predictability.

He cranks his megaphone as high as it will go and screams in a grating, piercing voice. I don’t understand why anyone ever buys his eggs, but God help you if you ever do it and then stop, because then what he does is park outside your home every single morning at 6 a.m. and scream your name. That’s why I’ve never given him a piece of my mind.

Without any doubt, from here to eternity, he would park in front of our house daily and yell, “Griiiiiiiiiiiiinga. Griiiiiiiiinga. Gringagringagringagringa,” or something much worse. No one wants to mess with the guy with all the eggs.

But someday, I swear I’ll find some huevos of my own. I’ll run out to his car and rip his megaphone from the roof. I’ll grab his disease-ridden, heat-addled eggs and crack them into the megaphone’s horn (since this is my imagination, he will somehow be unable to intervene until the whole thing is chock-full of a nasty soup).

I’ll then dunk his head in there like a thuggish high-school bully until he limps away, nauseated, unable to stand the sight of megaphones or eggs for the rest of his life, one menace to society who will no longer roam the streets.

In this fantasy, my neighbors, who have emerged from their homes in awe, will break into a slow clap. I’ll nod in a humble yet noble way, brush the eggshells from my hands, and take a dignified victory stroll through this hard-won kingdom of peace and harmony. As I pass the little cluster of men who always stand and talk in front of the pulpería, I’ll overhear their conversation despite myself.

“Mae, esa gringa sí tiene huevos,” someone will say admiringly.

“Pues sí, huevón.”

“It was about time for somebody to ponerle huevos and take care of that hij%&#$%&.”

“Pues sí, mae, qué mae más huevón.”

The pulpero will look at my retreating figure. “I should do something for that inspiring and selfless woman. Maybe a lifetime supply of eggs?”

“Of course, mae. That, and maybe a statue.”

“Diay, sí,” they’ll all say in unison. “Manda huevo.”

Recommended: The real secret of the world’s happiest country – grapes and MacGyver

Read previous Maeology columns here.

Katherine Stanley Obando is a freelance writer, translator, former teacher and academic director of JumpStart Costa Rica. She lives in San José.