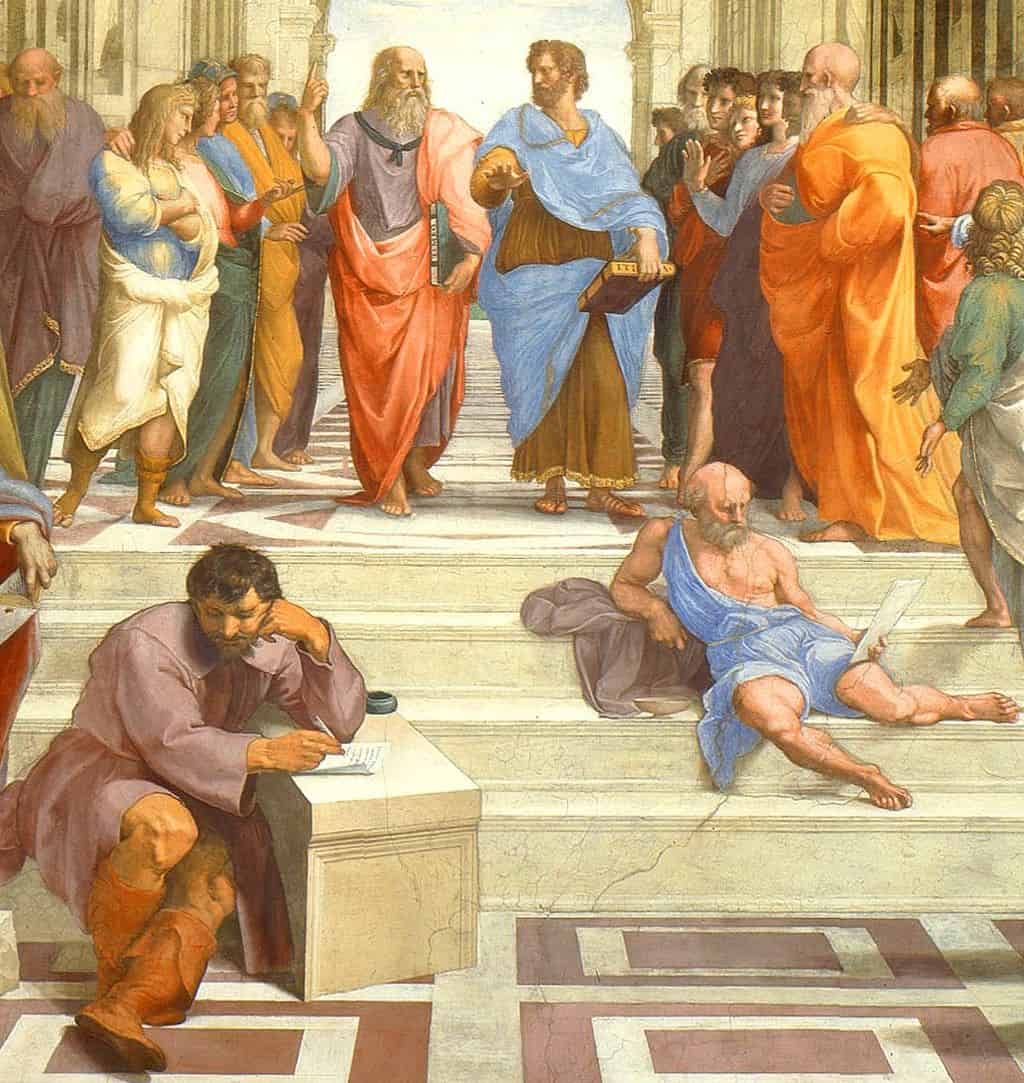

Since Plato penned “The Republic,” students of government have been asking of those who govern: “Who guards the guardians?”

In Costa Rica, the answer to that question is the Defensoría de los Habitantes, or Ombudsman’s Office. Since 1982, this office has been charged with protecting citizens’ rights, and it has the power to investigate public abuse of power and to initiate judicial proceedings against those who commit the abuses. But what happens when the person charged with protecting the citizens is herself suspected of committing abuses?

Ofelia Taitelbaum, Costa Rica’s ombudswoman has been ensnared in a media sting that has uncovered alleged tax fraud and tax evasion. As a result, many members of the legislature called for her resignation, which she delivered on Monday.

First appointed by the legislature under the administration of President Óscar Arias and reappointed this year over objections by many in her own party, Taitelbaum’s tenure has been marked by support for many progressive causes, including in vitro fertilization and an expansion of the rights of lesbians and gays in Costa Rica.

But reminiscent of the many scandals that plagued the previous administrations that brought her to the office, Taitelbaum’s fall is attributable not to the conservative and religious forces she claims are out to get her. It isn’t her progressive stand on controversial issues that has led to her current situation, but rather something more mundane and banal: private greed and personal arrogance.

The story begins at the end of 2013, when María de los Ángeles Otárola Soto, a 51-year-old seamstress from San Carlos hoped to be included in her son’s health insurance policy at the Social Security System, or Caja. Her request was denied because she supposedly already had reported economic earnings and paid taxes on them at the Tax Administration. When Otárola inquired what those earnings were, she learned that she had provided professional advice and services to a company called Inversiones Beyof, one of three corporations that lists Ofelia Taitelbaum as a partner.

Furthermore, these earnings date as far back as 2004. Otárola assured reporters who arrived to interview her that this could not be the case, because she had never finished grade school and was only qualified to give advice on cleaning windows and floors.

For Otárola, the relevant issue was that because the Caja would not allow her to be included in her son’s policy, she would have to pay for her own insurance. That insurance would cost a considerable amount because it had been reported to the tax agency that she has earned millions of colones in previous years.

Taking the prize for “Worst Possible Time to Initiate a Cover-Up,” Taitelbaum called Doña María precisely when representatives of the news media were interviewing her. Reporters recorded the call. In that recording, Taitelbaum allegedly can be heard asking Otárola to lie to reporters and claim she had received payment for professional consultations in the past. Taitelbaum also allegedly asked Otárola to say she had not received payments in over a year, warning the seamstress that if she didn’t lie, the reporter would make life “complicated” for Taitelbaum.

In an almost textbook definition of quid pro quo, Taitelbaum can be heard promising to pay the Caja for Otárola and to help her secure a disability pension in exchange for Otárola’s help in the proposed cover-up of Taitelbaum’s alleged violation of Costa Rican tax law.

Tax evasion is an all-too-common practice by the wealthy in every country. It is perhaps the most humdrum of crimes against the state, begging the question: Why would those with a career in politics or public service even attempt it?

As the ombudswoman for the people of Costa Rica, Taitelbaum is charged with ensuring that laws are respected, that citizen’s rights are protected and that Costa Rica’s political institutions do not overstep their authority. Instead, she allegedly has sought to defraud the Tax Administration and the Caja in an attempt to evade taxes owed to the people of Costa Rica – the same people she has been empowered to protect and serve. Personal greed is part of the problem, but as the facts surrounding this case emerge, another possible explanation presents itself: arrogance of the powerful.

In many petty crimes committed by public officeholders, the attempted cover-up is worse than the original offense and often leads to the office-holder’s downfall. This will likely be the case with Costa Rica’s ombudswoman. More troubling than the alleged personal greed revealed by the attempted tax evasion is Taitelbaum’s arrogant treatment of Doña María, who she apparently views as little more than a means to an end, a pawn in a scheme.

If the audio tape and Doña María’s story are to be believed, Otárola had no knowledge that Taitelbaum was using her to avoid paying taxes to the same government that pays Taitelbaum’s salary. Instead, the woman charged with protecting the rights of the citizens against abuses by government authority can now be heard on tape trying to coerce Otárola to be an accomplice in the covering up of Taitelbaum’s craven practice of avoiding paying the taxes she owes to the public treasury.

Evasion of paying taxes for personal gain, an arrogant lack of respect for the rights of others and the apparent treatment of citizens as little more than a means to one’s personal ends obviously do not make the best résumé for the job of ombudswoman. Indeed, it is to prevent and defend against such abuses that the office exists. Her own lack of respect for the institutions of government and the rights of citizens make it clear that Ofelia Taitelbaum is not the answer to the question posed by Plato’s critics: “Who will guard the guardians?”

Unfortunately, Taitelbaum’s behavior in this case seems more reminiscent of the warning offered by Friedrich Nietzsche to those who might do battle against lawbreakers and evildoers: “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

Gary L. Lehring is a professor of government at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. He is on sabbatical in Costa Rica.