Lawrence Walsh, the former U.S. prosecutor who spent seven years investigating officials in President Ronald Reagan’s administration for their roles in the Iran-Contra scandal, has died. He was 102.

His death was confirmed by two former aides, Guy Struve and Mary Belcher, the Associated Press reported. He died Wednesday at his home in Oklahoma City after a brief illness.

Best known for the Iran-Contra probe in the 1980s, Walsh had a distinguished six-decade career in law and public service. He was a racket-busting New York prosecutor, a federal judge, a deputy U.S. attorney general under President Dwight Eisenhower, a Wall Street lawyer with Fortune 500 clients, president of the American Bar Association and a negotiator during the Vietnam War peace talks.

At almost 75, he was called out of semi-retirement to probe the Iran-Contra affair, the clandestine plot to sell arms to Iran — in violation of an embargo — in return for help in obtaining the release of U.S. hostages in Lebanon. The funds were then funneled to right-wing rebels in Nicaragua, which was prohibited by an act of Congress.

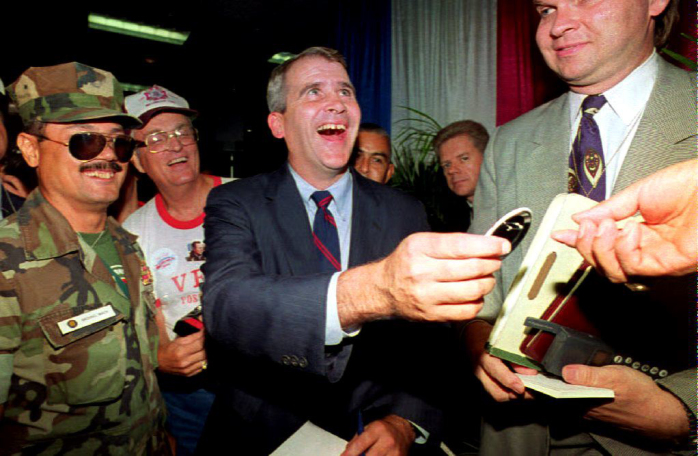

The affair included a cast of characters out of a spy novel: Oliver North, the Marine lieutenant colonel and national security aide who organized the scheme; his blonde secretary, Fawn Hall, who shredded key documents and smuggled out other papers hidden in her boots; John Poindexter, the national security adviser, Navy vice admiral and North’s boss; and Albert Hakim, an Iranian arms dealer with Swiss bank accounts, who died in 2003.

Walsh charged 14 people with criminal offenses, mostly for lying or withholding information from Congress. Eleven pleaded guilty or were convicted, though the two most high-profile targets, North and Poindexter, had their convictions overturned on appeal because their testimony to Congress under grants of immunity may have tainted the prosecution’s evidence.

Former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, charged with lying to Congress, was pardoned on Christmas Eve 1992 by President George H.W. Bush, a lame duck in his final weeks in office. Walsh was furious at Bush and suggested that the pardon may have been related to the former vice president’s own role in the affair. Weinberger died in 2006.

Walsh’s final report stated, “The criminal investigation of Bush was regrettably incomplete.”

The 1,200-page report, released in January 1994, criticized Reagan for helping to cover up the scandal but found he had done nothing illegal.

Walsh’s tireless pursuit of the investigation over two administrations led some critics to compare him to such obsessed literary characters as Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab or Victor Hugo’s Inspector Javert. Fellow Republicans accused him of spending seven years on a “fishing expedition.”

“Walsh was an honorable prosecutor who lost his way during a harrowing odyssey frustrated by Reagan’s forgetfulness, Poindexter’s code of silence and the congressional grants of immunity,” Lou Cannon wrote in the 2001 edition of his biography, “President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime.”

In a 1997 article for the online magazine Slate, editor Jacob Weisberg called Walsh “a maddening plodder and a stickler for detail, with no ability to play politics or work the media.”

“Like a pit bull on Prozac, he clung to the trousers long after the leg was gone,” Weisberg wrote.

Lawrence Edward Walsh was born on Jan. 8, 1912, in a small fishing village in Nova Scotia, where his father was a family doctor. He was raised in Queens, New York, and earned a law degree at Columbia Law School in 1935.

Though he sought to become an estate lawyer, Walsh joined a special state investigation into corruption among Brooklyn prosecutors.

In 1937, Republican Thomas Dewey was elected Manhattan district attorney, beating the candidate backed by the Democratic machine. Dewey tapped Walsh to join his staff of 70 assistant district attorneys being assembled to target corrupt politicians and mobsters. Dewey’s eager young attorneys became known as “the Boy Scouts.”

“Dewey was looking for lawyers with a Republican background and prosecutorial experience,” Walsh told the Washington Post in 1987. “There weren’t too many around because the Democrats had been in power so long. I filled the bill.”

He was paired with William P. Rogers, who would later serve as U.S. attorney general under Eisenhower and secretary of state under President Richard Nixon.

Walsh was “a soft-sell prosecutor; he wasn’t bombastic and there wasn’t much arm-waving, but at the same time he was forceful,” Rogers told the New York Times in 1987. Rogers died in 2001.

In 1941, Walsh left the DA’s office to join the New York law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell. The next year Dewey was elected governor of New York and chose Walsh as his assistant counsel and later his chief counsel. Walsh also worked on Dewey’s unsuccessful 1948 presidential bid against Harry S. Truman.

Eisenhower appointed Walsh to a federal judgeship in Manhattan in 1954, and when Rogers became U.S. attorney general he asked his former colleague to join him as chief deputy. At the Justice Department, Walsh oversaw the selection of federal judges and the integration of public schools in Little Rock, Ark.

During the 1960 presidential campaign, according to the New York Times, Eisenhower wrote a confidential memo to Nixon asking him to consider Walsh for the attorney general’s post. When Nixon lost, Walsh returned to Davis Polk.

Walsh served as president of the American Bar Association for the 1966-1967 term. He came under fire in 1969 when he led the group’s committee that found Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell qualified for the U.S. Supreme Court. The two Nixon appointees were rejected by the Senate.

He served as Henry Cabot Lodge’s deputy during the peace talks with North Vietnam in 1969.

In December 1986, a federal court in Washington selected Walsh to investigate Iran-Contra. By then he had been living in Oklahoma City for five years in semi-retirement.

The New York Times, in praising the decision, said Walsh combines “worldly experience with high ethical standards.”

As the investigation dragged on, Walsh was criticized by fellow Republicans. He obtained an indictment of Weinberger just prior to the 1992 presidential election, in which Bill Clinton defeated President Bush. The timing was assailed by Bush supporters, with some saying it cost him the election.

“Nobody was thinking about elections, as strange as that may seem,” Walsh told Cannon years later.

In his 1997 book, “Firewall: The Iran-Contra Conspiracy and Cover-up,” Walsh said his probe was undermined by Congress’s decision to grant immunity to North and Poindexter. He said he was considering indicting Reagan in late 1992 but never found proof the president was lying when he testified that he hadn’t known about the diversion of money to the Contras.

Walsh said he believed that Reagan, who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease before his death in 2004, could no longer remember details related to the investigation when Walsh interviewed him in California in 1992.

Reagan “would grasp at things that he would try to remember,” Walsh told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2004. “One was about being with Gorbachev in Geneva. Another was about a conversation with Margaret Thatcher. He was obviously grabbing at things that had left a deeper imprint on his memory.

”He took me to the window and showed me all of the buildings in Los Angeles, explained them to me,” Walsh said. ”It was a very moving experience.”

Walsh had two children with his first wife, Maxine Winton, who died in 1964. He and his second wife, Mary Alma Porter, married in 1965 and had a daughter.

© 2014, Bloomberg News