On a wet September morning in La Unión, a sparsely populated town in Costa Rica’s northeast, Rolando Álvarez and his two young sons directed their horses into the jungle. For the youngest son, Jean Carlos, 10, the ride was tinged with excitement and dread. His small horse powered over the trail and sent mud flying, and the bouncing boy strained to see through twisting foliage.

Soon they would arrive at the trap. The boy’s dog Coco would be in one compartment. If the trap worked, a jaguar would be in the other compartment, unable to get to the dog. If the trap worked.

For almost a month, the Álvarez boys had been making this trip, and there had been no jaguar. Around the town, the neighbors also had been vigilant, particularly those with livestock. They weren’t sure why a jaguar moved out of its territory in Caño Negro Wildlife Refuge and began feasting on their small cows. All they knew was that eight attacks occurred in La Unión between February and September. Almost all of them took place on small farms. For some campesinos, losing just one cow meant bankruptcy.

It’s not a new conflict in Costa Rica, but until recently, problematic jungle cats typically met their match in machete-wielding farmers. So the trap was a different approach. The conservationists disapproved, saying the trap could harm the jaguar and leave the community vulnerable to attacks. But they also knew it was a sign of change.

The trap was an effort to save the cattle. But also to save the jaguar.

*

The conflict between farmers and jungle cats began as soon as the Spaniards unloaded their cattle on American territory. The cows quickly became prey for the region’s jaguars and pumas, and the killing of big cats became common, in some areas even recreational. But mostly farmers killed jungle cats to protect their herds.

The first documented case appeared in the Spanish-language daily La Nación in 1962. The story described how a ferocious tiger decimated cattle near Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, and explained that an area farmer, José Yunis, was offering ₡1,000 (about $150 in 1962) to anyone who could hunt and kill it.

The misnomer “tigre,” or tiger, is still used to describe jaguars today, and their bad reputation with farmers also stuck.

“Time has passed, things have changed, but the rancher has always seen the tiger, or the jaguar, as an enemy,” said Daniel Corrales, the director of Costa Rica’s jungle cat and livestock conflict program for Panthera, the world’s leading jungle cat conservation group. “Even if it was a puma that killed their cows, even if it was a coyote, the farmer will always say it was a jaguar because to a farmer the jaguar is always at fault.”

As Costa Rica grew, so did the number of attacks. In the 1970s, two misguided government programs brought the problem to its apex.

“They had the best intentions,” Corrales said, “but they ended up creating the perfect storm for human-cat conflict.”

That decade Costa Rica began homesteading, or giving land to farmers willing to brave the nation’s forests in search of land to develop. Cattle farms began sprouting up in the most inhospitable of places. To this day, it is common to spot a cow pasture in the middle of thick Costa Rican jungle, or on the side of a steep mountain.

At the same time that farmers were setting out to seek their fortunes, the country’s conservation movement was beginning to take hold. The government designated protected areas and refuges, and farmers set up shop on their outskirts.

The result was a country of expansive green spaces surrounded by clear-cut farms. Protected areas were teeming with wildlife but had become islands, trapping animals within their boundaries. When jungle cats were forced out of their sanctuaries, usually due to lack of resources or territory disputes with other cats, they would now encounter crops and cows.

Despite Costa Rica’s abundance of national parks, the importance of biological corridors – small forested routes between larger patches of jungle that allow animals to move between protected areas – was never addressed. As shown by the attacks in Caño Negro, it remains largely ignored today.

It’s difficult to say what prompted the jaguar to begin hunting in La Unión, but experts believe pineapple is to blame. In recent years, plantations replaced nearby wildlife corridors, preventing the wayward jaguar from returning to its natural habitat.

“Pineapple plantations have really expanded in that area in the last few years,” said Esther Pomareda, a biologist at the Las Pumas Rescue Center and the expert most closely involved in La Unión. “As far as anyone knows, jaguars won’t cross a field of pineapple.”

Other recognized threats to Costa Rica’s big cats include deforestation, urban development and hunting. These practices drive cats out of the 40 square kilometers of jungle they typically inhabit, and into the human world.

This has taken its toll on the jaguar population and it is now endangered through most of its territory. An estimated 400,000 jaguars once roamed the forests of the Americas, and now experts believe their numbers have declined to about 14,000.

“Today, where can you find an area of that size that doesn’t have a man with a chicken somewhere?” asked Encar Cartia, one of the founders of the Jaguar Rescue Center on the Caribbean’s Playa Chiquita. “There just simply isn’t space.”

*

In La Unión, the first attack happened on Valentine’s Day.

Gerardo Portugués rode out into the pastures to round up his cattle. A headcount revealed that one was missing, a small calf. He headed up the mountain to look for it and found the animal lying on its side near the edge of the jungle.

She was covered in blood and a chunk of her chest was missing. Portugués had never seen anything like it. The neighbors came, took pictures and called the Environment Ministry.

Of Costa Rica’s six jungle cat species, only the jaguar and the puma can take down a cow. Because of pumas’ smaller stature, they usually prey on livestock younger than eight months. But large jaguars can take down 800-pound bulls.

An inspector came to analyze the scene. He noted the calf’s damaged head, her devoured chest and the defined, round footprints surrounding the carcass. The assailant was a jaguar.

To those with experience, a jaguar attack is often recognizable for its brutality. Another La Unión farmer said his dead animal appeared “as though someone had carved out a chunk of its throat with a machete.” The jaguar’s silent stalking makes it even more terrifying.

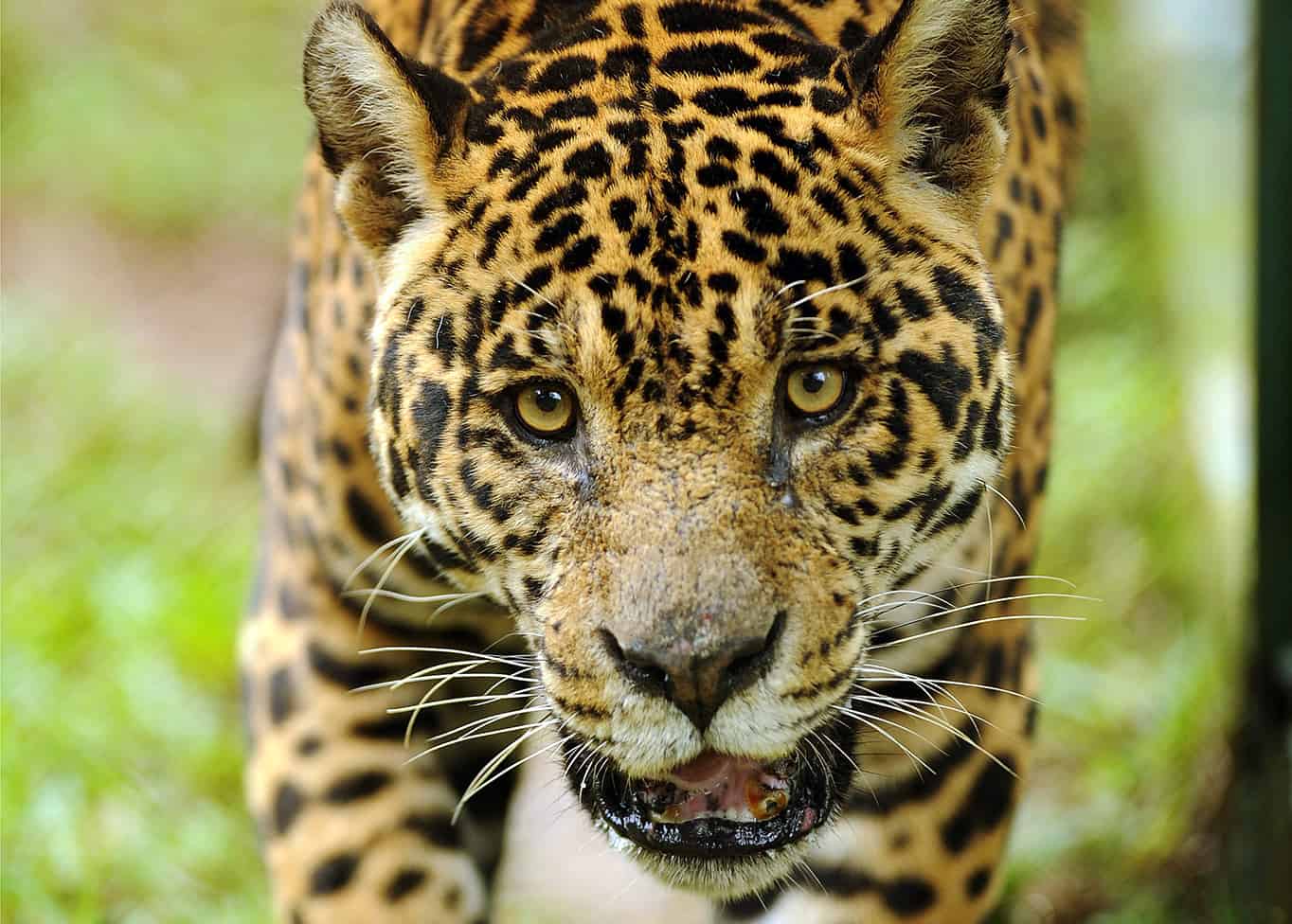

Though the jaguar is the third biggest cat in the world (behind the lion and the tiger), it has the most powerful jaw. Jaguars can bite down with nearly 2,000 pounds of force, strong enough to crush the skull of their prey. This enables the cats to attack from behind, surprising the target.

In a rare sighting, Rolando Álvarez remembers being paralyzed with fear.

“I saw it walking across one of the fields, low to the ground,” he said. “At first I couldn’t move. Seeing one is just such an intense feeling.”

Although Jaguars rarely attack humans, and they are actually the least likely of all big cat species to do so, fear prevails in much of the country.

“Most people kill jaguars because they are misinformed,” Pomareda said. “People think that if it attacks cows, it will attack them or their children.”

Other cat killers are motivated less by fear and more by circumstance.

“Many studies break it down to simple economics,” said Ronit Amit, head of the people and animals department at the environmental organization Guanacaste Fellowship. “The cat is taking away the farmer’s money. The farmer doesn’t have much money. The easiest solution is to kill the cat.”

Worsening matters, jungle cats seem attracted to small farms in the same way tornadoes seem to target trailer parks. A large percentage of reported attacks occur in farms of less than two hectares and with fewer than 20 cows.

“The only thing I was thinking was, ‘well now I have to deal with that loss,’” said La Unión farmer Jorge Chávez, who lost one of his 13 cows to the jaguar.

For the farmers pushed to the brink, Costa Rica still has its jaguar hunters. Until recently, a trio of brothers who called themselves the “hermanos tigres” filled this role in the Caño Negro area. Their job might sound particularly arduous, but it’s really not, Corrales said.

Though a jaguar’s size allows it to take down large animals, its stomach is not large enough to eat a cow in one sitting. After eating its fill, a jaguar will usually head to the forest to rest during the day then come back the following night to finish.

A good shot can sit with a gun until the jaguar returns. The less bold can sprinkle lethal poison over the second half of the meal.

For decades, farmers killed jaguars out of fear. But now a new fear is taking hold.

In 1992, a new Costa Rican wildlife law criminalized killing animals in danger of extinction, and a 2013 hunting ban set a $3,000 fine for sport hunters. This hunting restriction is saving jaguars, but it’s also complicating farmers’ problems with predators.

They now face a tough choice: Let the cat live at the risk of losing their livestock, or kill the cat, and risk a hefty fine and criminal charges.

“We started at zero, but we are starting to develop solutions to the problem,” Amit said. “We all have the same goal: no dead animals.”

*

Alejandro Padilla has loved horses his entire life. Unabashed by his obsession, Padilla always sports riding boots, a belt buckle engraved with a horse and his prize possession, a necklace carved from horse bone.

“I hope when I die that they bury me with this,” he said. “I want to take a horse to the other side with me.”

As the caretaker for the 38 horses at the remote Carolina Lodge, Padilla is constantly preoccupied by the area’s pumas, which are known for attacking small horses. In August, his concern was Besito, the lodge’s week-old foal.

Besito was skittish, constantly cowering near his mother. Long ago, Padilla figured out how to take advantage of the horses’ natural instincts to keep the pumas away.

“Two of our horses are defensive of the young ones,” he explained. “At night I just put Besito in the corral with those two horses and they will scare away anything that comes by.”

According to Corrales, Panthera has begun encouraging farmers to keep donkeys and water buffalos with their cows to protect them from cats.

“If a predator comes at night, a donkey will begin making noise that both scares the jaguar and warns the cows,” he said. “Water buffalos are defensive and they will fight a cat to protect the herd.”

Scare tactics are just one method farmers have begun using to deter cats, and for the past several years, nongovernmental organizations like Panthera have been helping farmers implement them.

Panthera works with more than 15 farms along three of Costa Rica’s biological corridors. Not one of the farms had an attack after Corrales and his team installed cat deterrents.

Most of these preventative measures (electric fences, motion-activated lights) are intuitive, but the NGO is constantly innovating.

“My favorite is the pizza system,” Corrales said, referring to several farms where Panthera divided the pasture into fenced wedges with a corral in the middle.

At night, the cows sleep safely in the center corral. During the day, they eat in one of the pasture’s divided sections. After the pasture in that wedge is depleted, farmers will let the cows into the next wedge, working in a circle until the cows return to the original, replenished wedge. The system lets farmers safely contain their cows at night without the time-consuming task of rounding up animals from an entire pasture.

Amit, who used to run a livestock and farmer program at Costa Rica’s National University, described other creative ways farmers protect their herds.

“Scare-jaguars,” or sacks dressed as humans and hung from trees, worked on one farm. Another used shiny ribbons that blew in the wind. But these methods have seen inconsistent results.

“One farmer put a radio in the corral and played this scandalous music to make the jaguar think there was a human presence,” Amit said. “But when his neighbor tried the same thing, he chose really beautiful music and that night the jaguar ate one of his cows.”

While Panthera favors preventative measures, other organizations focus on incentives.

Based in the wild southern Pacific town of Puerto Jiménez, the jungle cat organization Yaguará operates a compensation program for farmers whose cows have been killed by jungle cats. The organization has offered “jaguar insurance” since 2009, and has made more than 57 payments to farmers who have lost livestock but allowed the perpetrator to live.

Even though these organizations have helped farmers, there are limits in funding and personnel. Ranchers with little money or know-how can rarely solve their own problem without killing the cat. According to Pomareda, Costa Rica has 17 hot spots for wild cat predation.

“The hardest part of my job is to turn down a farmer who needs help,” Corrales said. “The only way this problem will ever be solved is if the government gets involved.”

La Unión fell into this unregulated territory, where only the Environment Ministry could respond. Without funding to help protect the farms, all the ministry inspector could do was inform La Unión farmers that they had a jaguar problem. Less than a month later, the government stepped in.

In September, the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC) designated 14 of its officials as members of Wildcat Conflict Response Unit (UACfel), Costa Rica’s first government-funded jungle cat and livestock program.

“The goal is to enable farmers to protect their animals,” said Rafael Gutiérrez, SINAC’s director. “The program covers the entire country, and will allow the government to actually put in some of these preventative measures for the farmers.”

*

Back at Álvarez’s home, three horses appear over the small slope behind the farm’s cattle pen. Drenched in rain and mud, the trio returns from the jaguar trap with the tiny dog, Coco, trailing behind. Jean Carlos leaps off his horse and gathers Coco in his arms, then takes him to play in a swamp near the house.

As for the jaguar, he didn’t come for Coco that night or any other. In fact, he never came for any more cows. It’s possible that the jaguar moved into new territory. It’s also possible he could return.

All the deterrents in the world won’t scare off some cats, referred to as “problem animals.” These are cats that have grown so accustomed to eating domestic animals that they no longer hunt. Some experts believe this could be the case with the La Unión jaguar.

A problem animal is the very last scenario in the new UACfel guide, and the only guideline is that the animal must be removed using a trap like Álvarez’s. The guide doesn’t say what happens next.