Rip currents – more commonly known as rip tides or undertows – are among the most dangerous and ubiquitous members of Costa Rica’s beach communities.

Many issues contribute to ocean-related deaths. Unpredictable, uncontrollable factors can produce dangerous situations in the water, as the devastating tsunami in Asia proved not long ago. Misinformation about the risks associated with swimming and not knowing how to swim contribute to the problem. Many beaches have no signs posted warning swimmers about potential dangers, because residents tear them down and businesses don’t want them for fear of driving off customers.

Alcohol consumption also plays a role. Finally, more than 80% of Costa Rica’s beaches have no lifeguard system, and those that do are extremely understaffed. But the root of most beach tragedies in the country is rip currents. Before entering the ocean in Costa Rica (or anywhere), it is necessary to have a basic understanding of rip currents.

Drowning is one of the leading cause of accidental death in Costa Rica. Available statistics indicate that 150-200 people drown every year in Costa Rica’s waters; 90% of these cases occur on just 30 of Costa Rica’s 600-some beaches. Of those who drown, more than four out of every five were caught in rip currents. With a little understanding of how the currents work, however, you can safely enjoy the ocean.

What Is a Rip Current?

This phenomenon is most often called a rip tide or undertow; however, these are misnomers.

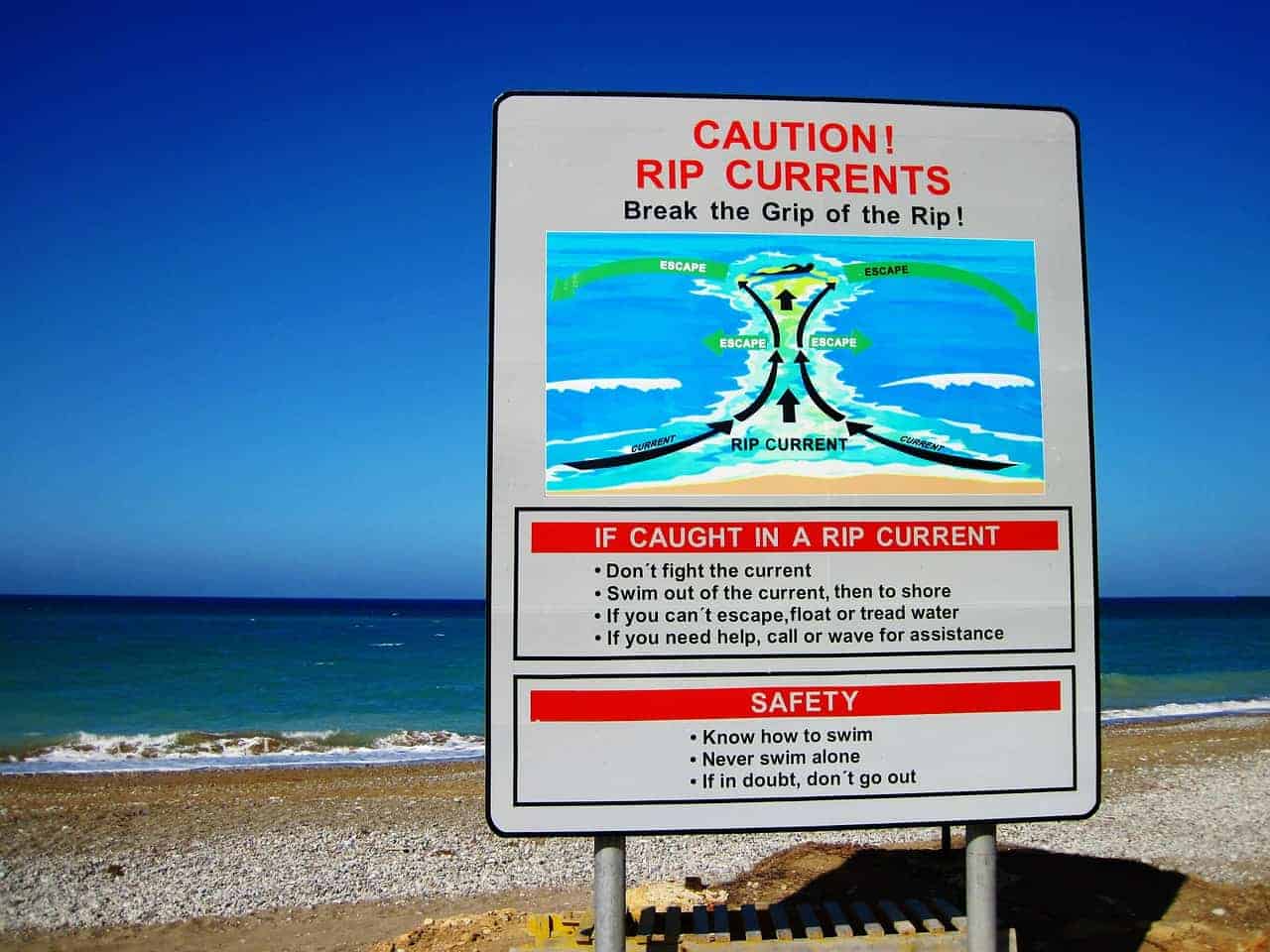

The flow of rip currents has little to do with the tide and it does not suck you under; it sucks you out. Rip currents form when there is an influx of water brought to the shore by waves. The accumulated water then seeks or creates a channel back to the sea in the area with the least resistance, usually between sand bars or at the deepest part ofthe ocean floor. This forms a current that acts like a swift river flowing away from shore at up to seven miles per hour – faster than an Olympic swimmer. A rip current consists of three parts:

- the feeder current

- the neck

- the head

The feeder current runs parallel to the beach and is the source of the out going water.

To gauge if you’re in a feeder current, you need to note landmark beach locations to keep oriented. If you thought you were stationary and suddenly find yourself 100 feet down shore, you could be in a feeder current. At the beginning of the channel back to sea starts the neck, which can be in water as shallow as your knees. If you feel the current pulling you out and you can touch bottom, walk parallel to the beach, jumping forward with each wave.

If the surf is rough, turn sideways as the waves come in so as not to lose balance. Keep moving until you’re out of the current. If you can’t touch bottom, make sure you can float by arching your back, tilting your head back and pointing your nose in the air. Then, without panicking, let the neck pull you out to the head, which is where the current dissipates. This is generally just beyond the breakers. Once out in more tranquil waters, swim calmly back to shore at a 45-degree angle around the neck to avoid being pulled back into the same current. Then you can ride the waves in.

The key is to remain calm. Whatever you do, do not attempt to swim against the current.

This will only tire you and cause more panic, which lowers your chances of getting out easily. This advice may sound simple and easy to follow, but in reality it is not. These are powerful, panic-inducing currents; when caught in one, thinking clearly and acting swiftly can be difficult. However, if you familiarize yourself with the procedures and understand how the currents work, reactions and instinct can take over, and you’ll be better able to get out safely.

Spotting a Rip Current

Rip currents may look like muddy rivers flowing away from the shore. If the ocean is rough with surf, foam may be present along the neck and head. Another warning sign is an area where waves don’t break but that is surrounded by breaking waves. Near hard, white-sand beaches, the currents may be harder to see. Always be wary when near a river estuary .A good test is to throw a buoyant object into the water and see where the current takes it.

And, as always, it’s a good idea to ask residents about the dangers of the beaches in their area. Remember, some beaches are frequented by surfers because the rip currents help them get out to the breakers; seeing people in the water doesn’t necessarily mean the beach is safe.

Types of Rip Currents

Four main types of rip currents exist.

- A type-one or fixed rip is usually found near manmade structures where the water moves around and the wave pattern is altered.These usually are in one set location and are strongly influenced by surf conditions. Look for them also at the cusp between two points on a beach.

- A type-two or flash rip is a short-duration, unpredictable current influenced by surf conditions.

- A type-three or permanent rip is focused around structures or river estuaries.

- A type-four or traveling rip is formed on long, open beaches and travels with the prevailing wave direction. These currents can be aided by the tide.

According to the daily La Nación, “when the tide moves from high to low, it is said that ‘the sea is emptying,’ and this is when rip tides are most dangerous because the tide pushes the waves in. If the tide is lowering(the sea is filling up) the rip currents are weaker because the sea is moving inward and that reduces the waves’ force.” Rip currents are most powerful three hours before high tide. Lifeguards in the country recommend waiting an hour before and after high tide to let the currents calm a bit.

Tide information can be found online and through residents. Ask around. Keep this information in mind before going for a swim or hitting the waves in Costa Rica. Knowing how to recognize and handle these currents can make your stay safer and more enjoyable. In memory of Greg Schrieber (1979-2002).